During my first year of postgraduate training in Family and Couples Therapy, my supervisor said something so simple and yet so surprising that it permanently shifted my sense of self. I was working with a couple that had been struggling with trust, closeness and commitment. My supervisor advised “Kacy, think about romantic love in terms of attachment”.

This theory of romantic love was influenced by her training in Emotionally Focused Couples Therapy, EFT (not to be confused with another therapeutic approach Emotional Freedom Techniques) which uses Attachment Theory as a basis for understanding intimate partner love and patterns. In reflecting on my own earlier romantic relationships using this lens, some of my past responses and reactions that had previously mystified or frustrated me, immediately began to make sense. I subsequently trained in EFT with Dr. Susan M. Johnson, one of the founders of this approach, and have been incorporating EFT with a number of my couples clients ever since.

Couples Therapy is an incredibly broad term. There are numerous theories, approaches and interventions that therapists utilize in supporting couples. EFT is just one of the many approaches in this work. Because of EFT’s foundation in Attachment Theory, its emphasis on emotional experience, and its framework that deliberately does not locate the couples challenges in any one partner, I have often felt that it intersected meaningfully with themes of adoption and intimacy for those of us who are adoptees.

EFT was developed in the 1980’s, partially to provide space for a more humanistic approach to couples therapy. It was named Emotionally Focused Couples Therapy to emphasize the importance of “emotion and emotional communication in the organization of patterns of interaction and key defining experiences in close relationships. It also focused on emotion as a powerful and often necessary agent of change, rather than as simply part of the problem of marital distress.” (Johnson, 2004). EFT is an evidenced based treatment and often implemented as a short term couples therapy with 8-20 sessions.

EFT and Theory of Love

Dr. Susan M. Johnson is a Canadian therapist and one of the main proponents of EFT. She has written several books about EFT and has trained thousands of therapists in this approach. She describes love in this way:

Dr. Susan M. Johnson is a Canadian therapist and one of the main proponents of EFT. She has written several books about EFT and has trained thousands of therapists in this approach. She describes love in this way:

“Love is in actuality the pinnacle of evolution, the most compelling survival mechanism of the human species. Not because it induces us to mate and reproduce. We do manage to mate without love! But because love drives us to bond emotionally with a precious few others who offer us safe haven from the storms of life. Love is our bulwark, designed to provide emotional protection so we can cope with the ups and downs of existence.” (Johnson, 2008)

EFT and Attachment Theory

EFT and Johnson’s work largely centers Attachment Theory as a way of understanding intimacy and our responses and emotional experience in romantic partnership. Please see last week’s article about Attachment Theory to understand about attachment styles in intimate partner relationships.

In EFT, attachment is used to understand styles of engagement rather than as an individually based disorder. In addition, EFT presumes that attachment styles, because they are developed in transaction are continually constructed and reconstructed in interactions with loved ones. As a result, EFT works to understand and explore attachment styles in couples and to break down unhelpful or even harmful feedback loops that have impacted the couple and to build more secure attachment bonds in the dynamic.

Emotion and EFT

Some forms of couples therapy work to deescalate emotional response in order to focus on more mindful communication. EFT utilizes a different stance that elevates the importance of emotion in the practice. EFT is very experiential in its use of and attunement to emotional experience. Guidano writes that “While thinking usually changes thoughts, only feeling can change emotion.” (Guidano, 1991). Johnson expresses that “Emotion is then the music in the dance of adult intimacy. When we change the music- we change the dance.” (Johnson, 2004). EFT utilizes an approach that is very present in the emotion of the couple and uses emotion that arises during the sessions to shift dynamics and meaning.

In EFT, emotion is often seen through the lens of attachment. For example pursuit and “angry criticism, viewed through the attachment lens, is most often an attempt to modify the other partner’s inaccessibility, and as a protest response to isolation and perceived abandonment by the partner. Avoidant withdrawal may be seen as an attempt to contain the interaction and regulate fears of rejection and confirmation of fears about the unlovable nature of the self.” (Johnson, 2004). Emotional responses, whether big or small, are placed within this context and make sense based on attachment needs.

Fear and uncertainty may activate attachment needs. If one member of a couple calls the other 10 times when their partner is 20 minutes late, that emotion is unpacked- maybe it was anger and fear that was activated by worry that they were isolated, alone, and unimportant to their partner. These are not considered small fears when we understand that attachment is a survival technique. Feeling seen, loved and known are not just good feelings but in fact, essential feelings for survival. Subsequently fighting for this or conversely fighting to avoid triggers that make us not feel this, makes sense within the context of Attachment Theory.

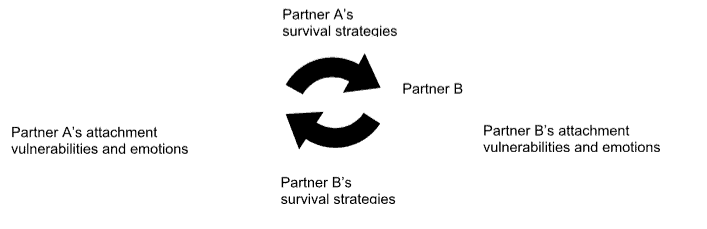

Understanding these patterns doesn’t mean that what is activated feels good or is sustainable or works for the relationship. It does mean, however, that a cycle of interaction within the couple can be tracked and placed within the context of the challenging patterns of interactions when these survival stances take over. A cycle of interaction can be mapped and drawn out.

Cycle of Interaction

This cycle in its nature acknowledges the experience and presence of both partners. The “problems” within the relationship are not just located within one person. The problem is reframed as a problematic cycle of interaction. Various things might trigger the cycle to engage- for example a partner may not return a phone call or a partner might ask whether you will wash the dishes. The triggers are not always obvious, like a partner lying or a partner having a secret affair.

Each partner can track the emotions and fears that arise and the stance or “survival strategy” (Scheinkman, 2004) they take in response. For example a partner that fears being isolated or unimportant or unlovable might pursue their partner for reassurance. Pursuit might look like 10 phone calls in 20 minutes or repeated questioning- maybe initially described by their partner as interrogation. A partner that fears being inadequate, incompetent or unlovable might withdraw in order to protect themself from these feelings and possibly with a hope to protect against escalation. Withdrawal might look like not returning phone calls, not saying anything, turning away from their partner- maybe initially described by their partner as stonewalling or silent treatment. Within the cycle, partners can track how the other’s survival strategies might then trigger their own attachment vulnerabilities and activate their own survival strategies.

Within EFT, the problem and focus turns to the cycle of interaction. Within this context, partners can engage in new ways of dialogue and experience that explores emotion, attachment, cycles and how these intersect (Johnson, EFT). Similarly to Narrative Therapy approaches, the cycle can be named and “externalized” (White, 2007)- placed outside of any individual person and can be worked on collaboratively.

Contraindications for EFT

EFT is often best utilized with couples who have some desire and commitment to improve their relationship dynamic and who have openness to understanding how they each have contributed to challenging cycles of interaction within their relationship. In research studies about EFT, when a partner had a “rigid lack of trust” in their partner, then EFT was less effective (Johnson, 2004). In addition, EFT is generally not recommended for couples who are separating. It is also not recommended for couples where abuse or intimate partner violence is present (Johnson, 2004).

What EFT Doesn’t Address

There are numerous factors that influence a couple’s dynamic. EFT doesn’t specifically address issues related to race, gender, privilege and systems of oppression that inherently inform and impact all of our identities. These themes may arise during exploration of attachment styles, emotional experience or the cycle of interaction but because they are not specifically noted or tracked through this practice, important pieces of work that impact a couple may not be addressed through this approach.

Adoptees and EFT

Because EFT has a focus on attachment style as a way of understanding responses and needs in a relationship, I believe EFT can be helpful for adoptees in intimate partner relationships. I have frequently worked with adoptees who have asked “Why do I do that?” or “Why can’t I stop doing that?” in their relationships when vulnerability is triggered. I think this lens of attachment can support adoptees in making sense of their patterns in relationships and simultaneously place struggles or challenges that surface within the relationship in a larger context that includes the experience of their partner.

EFT attempts to depathologize the idea of attachment- that it is not a disorder but instead is a normative response to experiences and relationships in life and can be influenced through intimate partner relationships. I think it is helpful for adoptees to think about attachment style as malleable and understandable, especially within a larger historical context where many adoptees have been labeled and diagnosed with Attachment Disorders.

Also, EFT highlights the belief that individuals can grow and learn and understand their own identity through being in partnership. I have heard from some adoptees that the idea of engaging in a relationship seems overwhelming or even potentially damaging if they haven’t unpacked their own individual identity more fully. I understand and respect this stance and I also appreciate how EFT assumes that self-identity can also be worked on through the process of being in relationship. The idea of more expansive possibilities rather than limiting choices feels important for those of us that are adoptees where choice and control are often painful themes.

Conclusion

EFT is an evidenced based and short-term, experiential couples therapy approach that supports couples in tuning in to their emotional experience, attachment vulnerabilities and their subsequent survival states that make up a piece of their joint cycle of interaction. EFT supports couples in experiencing their partnership in new ways and deescalating and shifting problematic cycles within their dynamic. You can find more information about EFT by visiting these websites:

International Centre for Excellence in Emotionally Focused Therapy (ICEEFT)

References:

Bretherton, I. (1992) The Origins of Attachment Theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth

Developmental Psychology, 28(5), 759-775.

Guidano, V.F. (1991) Affective Change Events in a Cognitive Therapy System Approach. In J.D. Safran & L. S. Greenberg (Eds.), Emotion Psychotherapy and Change (pp 50-82). New York: Guilford Press.

Johnson, S. M. (2002) Emotionally Focused Couple Therapy with Trauma Survivors: Strengthening Attachment Bonds. The Guilford Press.

Johnson, S. M. (2008) Hold Me Tight: Seven Conversation for a Lifetime of Love. Little, Brown and Company.

Johnson, S. M. (2004) The Practice of Emotionally Focused Couple Therapy: Creating Connection. Brunner-Routledge.

Scheinkman, M. And Fishbane, M. D. (2004) The Vulnerability Cycle: Working with Impasses in Couple Therapy Family Process, 43(3), 279-299.

White, M. (2007) Maps of Narrative Practice. W.W. Norton & Company.

Yip, J. (2017) Attachment Theory at Work: A Review and Directions for Future Research Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(2), 185-198.

About Kacy Ames

Kacy Ames is a Licensed Clinical Social Worker in New York City. She has a private practice where she meets with individuals, couples and families touched by adoption. She did her training in Family and Couples Therapy at the Ackerman Institute for the Family where she continues as a Project Associate in the Foster Care and Adoption Project. Kacy has run groups for adoptees through her private practice and has facilitated birth parent support groups through the Foster Care and Adoption Project. Kacy’s therapeutic approach focuses on family systems, narrative work and trauma informed practice with a social justice and racial justice lens. Kacy was adopted through transracial, inter country adoption. She was born in Korea and adopted by a white family in Massachusetts. Kacy is the parent of two children by birth. She currently resides and practices in New York City.